GUEST BLOGGER 12

ESSAY: KARL KEMPTON

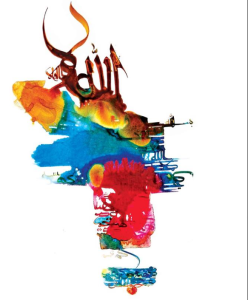

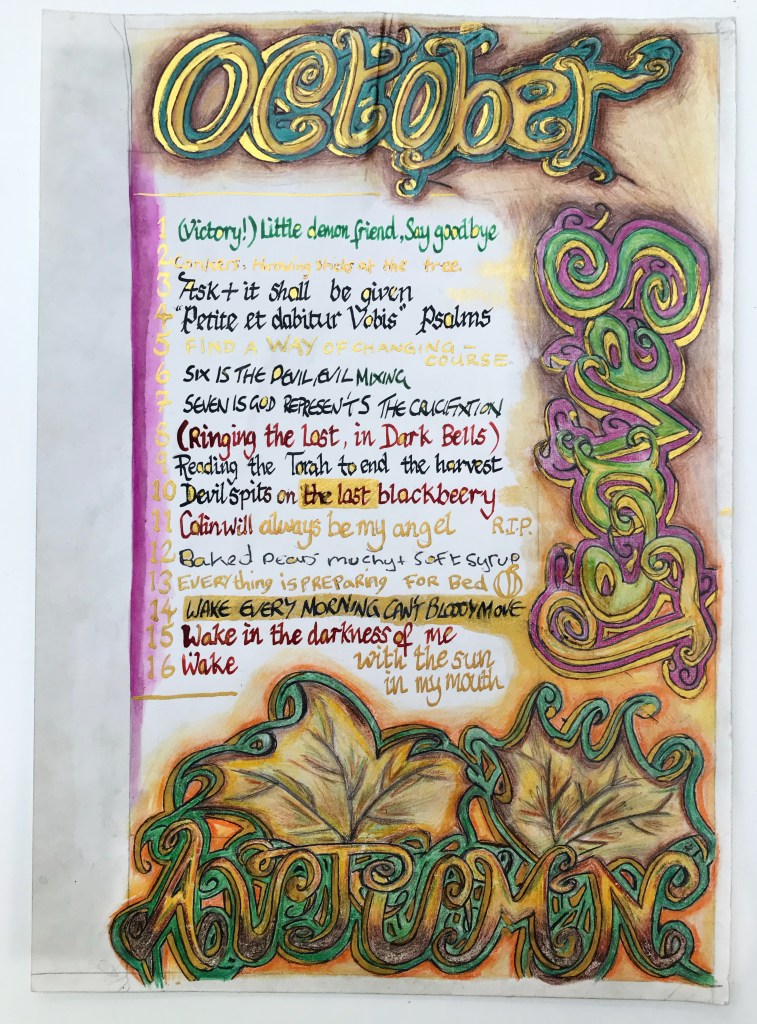

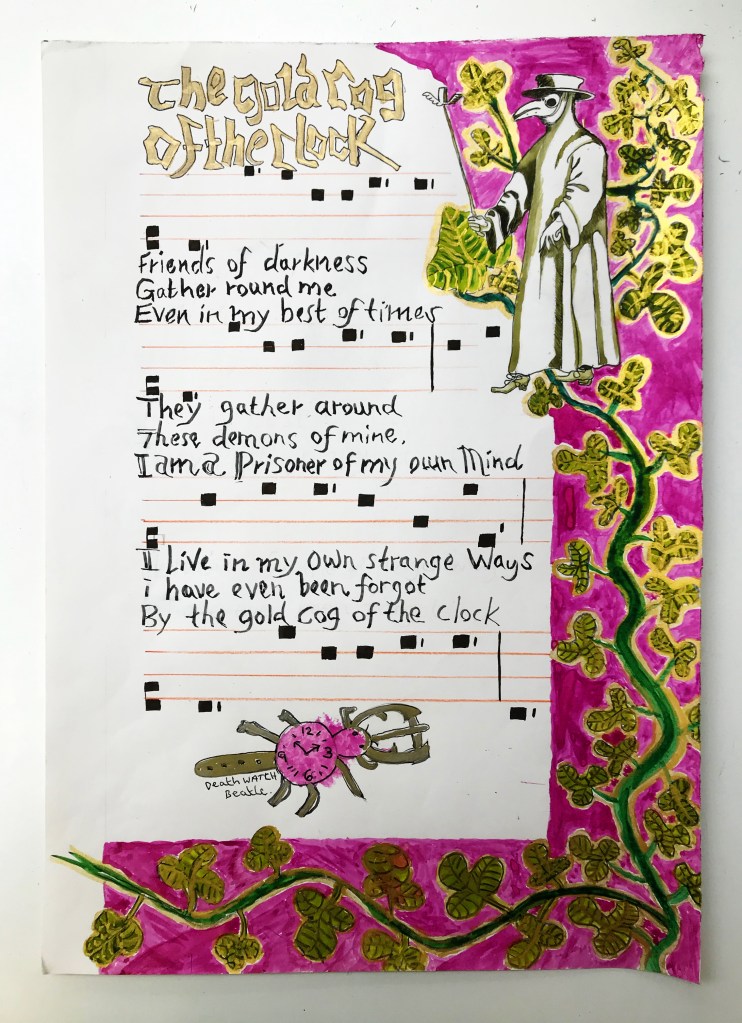

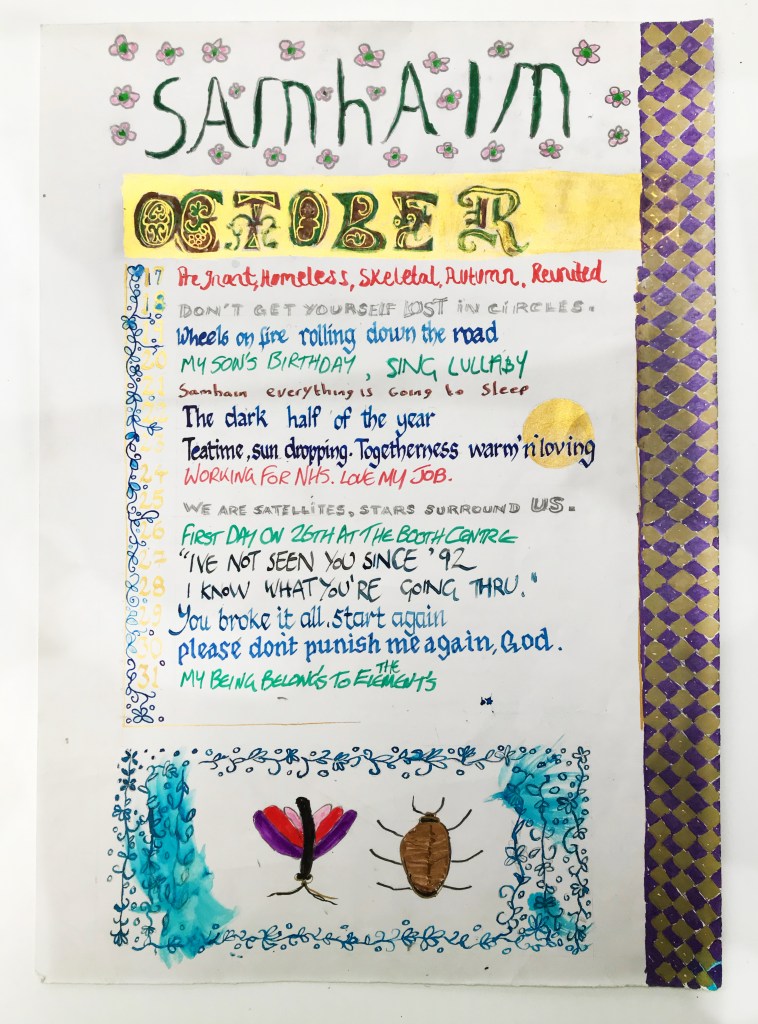

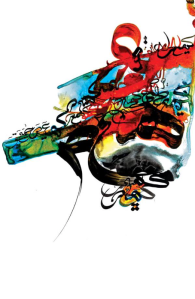

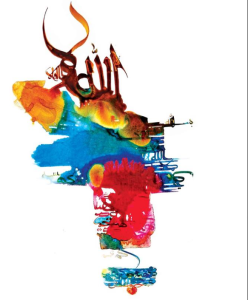

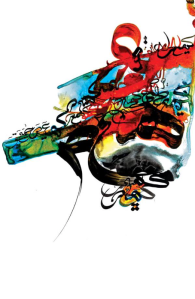

TEXT WORKS: MOHAMMAD ARIF KHAN

karl kempton’s a history of visual text art traces the deep roots of language art, finding poems for the eye in the ancient, the occluded and the disappeared. It was published by Apple Pie in 2018, as a ‘prequel’ to The Dark Would anthology, which itself grew from the Text Festival. A free PDF download of kempton’s book is here.

kempton’s account begins with newly-available prehistoric evidence, finds paths through clusters of religious and political influence across the globe and then moves into a long review of the 20th and 21st Centuries, from the Russian Avant Garde to the Stieglitz Circle, Concrete Poets to Conceptual Art, Arabic Word Painting, Iconographic Painting, and beyond. The book is unusual for finding nuances and practitioners who had been ignored, or erased. So we have Barzun’s story more than Apollinaire, we have Theosophy in the lineage, alongside Mallarmé we have the seers. Crucially, kempton includes non-Western narratives, and details the affect of spiritual practices — particularly Buddhist Ch’an and Zen, Sufism and American First People — on the gestation of language arts. Much of the book is an untold history: some practitioners discussed in it were suppressed by violence or persecution, for others the erasure has been more subtle. The book is most especially for those makers who have been “disappeared”, bringing them back to our eyes.

The blog Synapse International (Ed. kempton and Davenport) is an online Volume Two of illustrations, gathering a wide range of works by visual text practitioners from around the world, selected by guest editors.

(a history of visual text, publicity notes 2018)

And so. The spectrum of visual poetry and what passes as visual poetry continues to expand. But large numbers of visual text art works created before WWII were made by individuals who are now either forgotten, ignored or have been “disappeared” in ego-driven poetry conflicts between various camps. The primary division being between the egalitarian and the only-us. One of the intents of my 2005 essay VISUAL POETRY: A Brief History of Ancestral Roots and Modern Traditions (1) and its expansion into my long book in 2018 is bringing to light the missing-in-action.

Background

My 2005 web-published essay needed updating and links were broken. More information had been accumulated. The essay answered a question from Dan Waber concerning the differences between concrete and visual poetries, a question whose fullest answer became the book in 2018. In between, I was asked to write an introduction to a proposed visual poetry anthology, Renegade, a collection of international visual poetry & language arts (2) and realized I had to study the pre WWI Russian avant-garde.

No one had followed up on my suggestion for a multi-volume book on the history and developments of visual poetry; I decided to do it myself. I’d write an overview others could add to or correct where they saw shortcomings. I planned a free pdf for the interested with hot links to works doubling as an virtual anthology to avoid the maze of copyright laws. Had I known the road would take me on a six-year journey, I may not have begun. But I am richer in knowledge, meeting many new word painters and visual text artists. The book expanded the essay of 39 pages to 569.

Before 1900

The essay also provided an overview of the ancestry of visual text and poetry types before 1900, beginning with the origins of writing in rock art. In the early 1970s many poets in the country became interested in ethnopoetics, ch’an / zen and later sufism. But many sources remained untouched such as Marshack and Gimbutas, both of whom I closely read. Gimbutas’ theorized origins of proto-writing are to be found as signs in rock art, later-pottery and other portable objects. Her contention was that these early developments in the evolution of proto-writing to alphabets were ground breaking. With the old guard gone, new techniques in use, and new and expanded areas of research, new finds arrived on the web almost weekly, sometimes daily. I tried to keep up and add the more significant findings during the writing of the book. The most radical changes were the new views on the Neanderthal (though Gimbutas had nodded in their direction and for doing so was soundly rejected. She was actually decades in the forefront).

My first writings on the visual sources of inspirations for proto-writing and alphabets appeared in “visual poetry: definitions, context and problem of types,” Innovations I, 1991. Interests in archaeology, mythology, ethnopoetics, and spiritual traditions informed me of various pathways of early visual communication with their respective evolutions. I expanded the list of proto-writing and went deeper into detail, including suggestions for alternatives to the traditionally-accepted narrative of the development of signs becoming our alphabet. Concrete and visual poetries were constantly appearing in mail art collections and other publications; most of their alphabet-origin-works remained with the unquestioned Eurocentric view of pre-Greek, Phoenician South East Mediterranean, Egypt, Fertile Crescent and China fields. But, these areas were not probed for earlier developments. Among the geographical exceptions Karl Young (3) pointed with dexterity and detail to Meso-America as another unique origin. (4)

Calligraphy cannot be ignored. Each major religious area has its own forms of beauty and associated iconographics, some of which jumped from rock art to pottery to page. Calligraphy was a major visual text art until its demise caused by the printing press in Europe, contrary to its prominence in Islamic Culture and East Asia. The health of South Asian forms is mixed. In my book, the discussion on calligraphy follows a sequential development before 1900. A more detailed look at esoteric calligraphy is given in the last section. The historical development of the Science of Letters begins with Orpheus. Surprisingly, the Islamic Science of Letters influenced European visual text arts after WWII. “Surprisingly” because I find no direct discussion of this among visual poetics, only in collections of Arab language word painting. Members and associates of the Lettrists and Art Informal were Persian and Arab word painters. Out of Arab and Persian calligraphies after WWII came the development of word painting. Word painting found expression in America from the 1920s onward. I hope others will expand on its overview in my book.

Correcting visual poetry history

The third focus in the essay was an (ongoing) attempt to correct the historical record of concrete and visual poetry. Some, like my deceased friend Bob Grumman, held tightly to the accepted story promoted by concretists: Apollinaire to Cummings to American concrete. For me, this lineage ignores three areas of concrete poetry origin in the early 1950s influencing American concrete. It also ignores the earliest American visual poetry and text art composed before WWI within the Stieglitz Circle, published in 291, that also influenced European works by Picabia and others. It additionally ignores the Circle’s influence on portraiture in visual poetry, iconographic and word painting before WWI into the 1930s. The Circle was founded on photography, years before Kitason Katue, of the Japanese avant-garde group VOU, called for poets to replace the pen with a camera to flip objects into iconographic symbols for a wordless poetic. He too was a forerunner of concrete. (5)

Information available to me for the essay that I had previously trusted I correct in my book. For example, I expanded the discussion on the Circle to included short biographies and works of influence illustrating its larger significance in American visual text art into the 30s ignored or disappeared by concrete, neo-concrete (vispo’ers) and visual poets. Curiously, they were a New York City avant-garde later ignored by later groups centered in New York. Another correction was unraveling the self-glorification of the Brazilian Noigandres Group. If this was their only fault, I would have ignored it. They caught the virus of supremacy at all costs from a mix of Italian Futurism, Marxian or Hegelian dialectics, and rejecting-the-past nihilism. They allied themselves with factions of American concrete; this academic consolidation formed a self-appointed “avant-garde” promoting Noigandres concrete above all others. Then they participated in disappearing others’ histories contrary to their party line in this country (USA) as was done in Brazil by Noigandres.

The fourth focus, another part of correcting the histories, shines a light into the pit where historians of concrete poetry tossed individuals, to ensure their disappearance. In the essay, among others I point to, is the attempted erasure of the 1939 to 1948 visual poems of Kenneth Patchen that essentially form a checklist of types of concrete to come. It seems trying to prove originality leads to this behavior, even among poets who, ideally, are truth seekers, sayers and whose stance is truth to power. Seems I am an idealist.

My interest in correcting what I and some others considered the history of visual poetics began when I met Miriam Patchen, Kenneth Patchen’s widow, for an interview in 1978 for Kaldron 9. (6) Kenneth Patchen is considered by many in this country to be our William Blake. Yet, his work neither appears in American concrete poetry anthologies nor was he discussed or mentioned, not even in a footnote. Yet he was the forerunner of American concrete, proven with his numerous proto-concrete works from 1939 through 1948, before turning to his better-known picture poems. I remain disturbed and disgruntled with the responses from the anthology publishers and editors to my querying his disappearance, if they answered me at all. I also remain puzzled at the shoulder-shrug responses in the concrete and visual poetry communities. Are they keeping their heads low not to be seen by those they unwittingly give power to, the gatekeepers of the orthodox story, or do they not care about tradition, craft, beauty and truth?

I tasked myself to correct the record where necessary. Patchen, I discovered, was not an exception; the running total of the ignored and disappeared grew with my occasional research over the years. The problem of gender representation appears after WWII. Undervaluing or ignoring women characterizes the concrete anthologies where one or two women appear, token-like. Doris Cross and Betty Danon, both deceased, remain ignored by the American gatekeepers (Betty Danon on her work: “It will be given acknowledgement when you don’t care any more.”) (7) The body of works by Marilyn Rosenberg and K. S. Ernst are generally ignored. (8) My task of course challenges the American-gatekeeper “history.” Speaking truth to power in my environmental efforts led to death threats and a tapped phone. (9) Speaking truth to this “avant-garde” academic literati led only to ostracism. (10) Such was not the case for Harry Polkinhorn after the April 7-8, 1995 Yale conference, “Symphosophia: The End of Literature.” During his presentation of his paper, “Hyperotics: A Towards A Theory Of Experimental Poetry,” he announced the publication of Philadelpho Menezes’ Visuality: Trajectory of Contemporary Brazilian Poetry by SDSU Press. Publication in Brazil had been blocked by the Noigandres cartel. (11) Polkinhorn’s translation caused a ferocious and personal response by the academic concrete-language poetry clique. Polkinhorn left visual poetics creating a great loss in American translations from Spanish and Portuguese Latin American visual text arts.

Exchanges with Dan Waber, host of the website “minimalist concrete poetry,” (12) who published my article in 2005, (13) show Karl Young and I were not the only ones upset with the disappearance of Patchen and others from the anthologies. Dan was as appalled as Karl and others. kaldlron(.2), (14) the web site, came into being under the skilled guidance of Karl Young. (15) With the help of Harry Polkinhorn and its contributors we continued publishing the best works we could and provided context for the works, mainly with his articulate essays. The web site continues to provide numerous supporting sources for my essays. (See also the current Synapse International)

Orphism to Seers

Another vexed topic was the need for a term to categorize works of high quality imbued with (to my eyes at least) true vision, beauty and a spiritual root. In my essay I had decided on “Orphism” as a catch-all term, which had already been in use before WWI. Not having a deadline for the book allowed me to follow hinted and hidden trails seen in footnotes or between lines uncovering more overlooked, consciously disappeared or forgotten individuals, groups, and influences. I read closely the intents of the pre WWI avant-garde. I found an error in my essay regarding Orphism. Orphism’s actual founder was not Apollinaire, for whom it was attributed. I corrected this error, rightfully crediting Henri-Martin Barzun. (16) I also found and added seer painters and their works. Wanting a continuity within the history of visual poetry, I did not look for a new term. With Orphism as a category I listed a few individuals I thought presented works worthy of study by others — and for those new to visual poetry as possible role models. Coming across the writings of Henri-Martin Barzun in his American published books proselytizing Orphism, I came to learn his intent, and the intent of those associated with him: creating a new form of integrated art to lift culture and hence society to a higher level of awareness. Part of the original choice of the term Orphism was influenced by ethnopoetics where one finds the original function of the poet for her or his group, tribe or nation. (17)

Correcting this error along with deeper studies of various spiritual influences led me to ignored or rejected aspects of Platonic philosophy. (18) To understand the roots of contemporary Arab and Persian language word painting, I studied the biographies, writings and poetry of Sufi masters whose works formed the philosophy of the Science of Letters. It seems few visual poets and no (as far as I know) concrete poets were aware of the influence of the Science of Letters on the Lettrists and Art Informel. Platonic and esoteric philosophies influenced many of the pre WWI avant-garde, excluding the Italian Futurists who eventually, disastrously, embraced fascism. This material is of course associated with a baleful history, but the artistic influence exists and should be acknowledged, especially in this time of the rising far-right which thrives on invisibility, misunderstanding and code.

In the Islamic sphere hundreds of years ago many of these strands were woven into the Science of Letters that now informs many Arab and Persian language word painters. (19) Again, the influence of Islam is problematized by contemporary fundamentalism and the current Western societal responses to it. And once again, I believe, the word and its backstory needs to be made fully visible.

Pulling inspiration from iconographic spiritual symbols, except surface use for collage works, remains frowned upon in my country, the USA. The negativity is such even someone as fiercely independent and strong as Karl Young held back from publicly dipping into his spiritual tradition to compose works, fearful of the reactionary consequences from academic “avant-garde” peers. Karl’s father, alive during the 1990s and deeply loved by Karl, was a retired minister. In the 1960s their home was a target for attacks because he fought racism in Kenosha. Karl continued defending the “underdog” throughout his life against bullies, regardless of occupation. I got to know Karl intimately beginning in the late 80s through correspondence and then long phone conversations for which he was well known among his friends. He had been among the first to create a body of critical work supporting the emerging language poets. Later he became a champion of those they tried to erase or ignore.

What I did not explicitly discuss in my essay was beauty. Beauty had become pejorative. A sad commentary on our times and the avant-garde that not only are poets and artists fearful of attack or ostracism for expressing a form of spirituality but also for attempting to reach for beauty as part of a work. In my book I face toward “Beauty,” with a capital B, and link the discussion to what I see as the function of the visual text artist and poet, particularly in word painting the pervasive influence of the Science of Letters and Platonic philosophy.

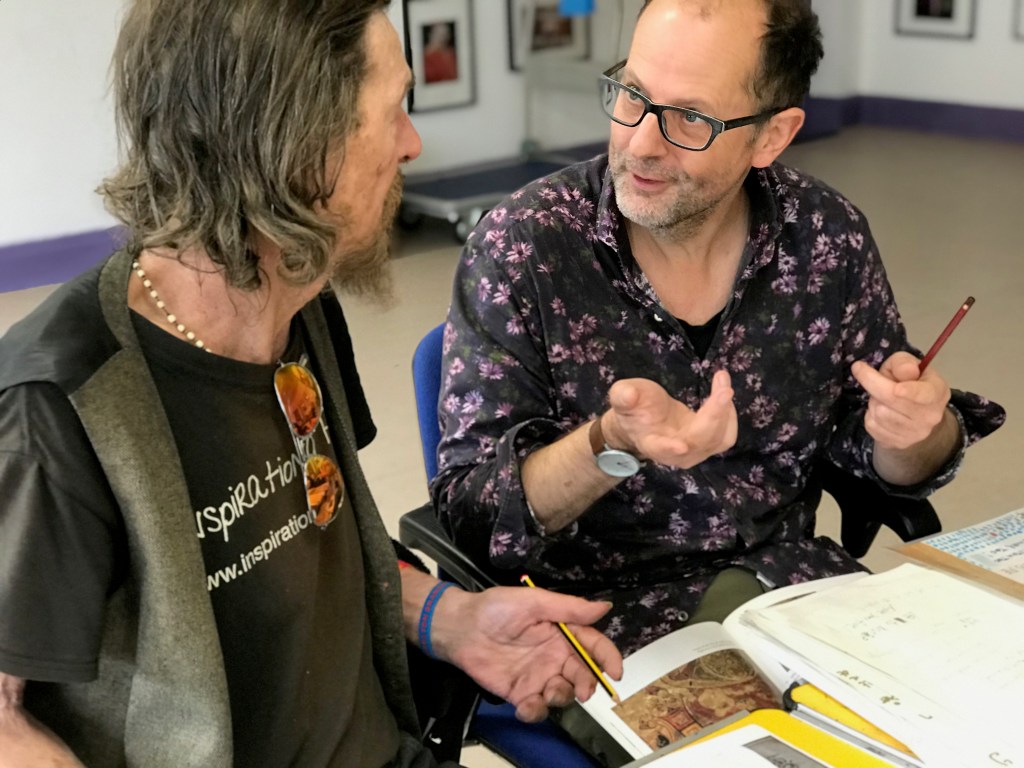

Orphism, as understood by Barzun and his colleagues, was a group not individual effort. While I consciously live removed from literary centers in a semi-rural area on the eastern edge of the Pacific Ocean in Central California , I often work with others, long distance in my poetics and short distance in environmental protection. The same process applied to writing the book. Originally, I planned the book without visual materials. This changed when Márton Koppány, who became my primary reader, introduced me to Philip Davenport. While Márton was my primary reader there remained areas of disagreement with some of my observations, views and conclusions. Philip eventually became the book’s publisher and a co-editor of the international visual text anthology, Synapse International, hosted by Anindya Ray of Kokata, the first of its kind hosted in India. This blog anthology was devised as an online Volume Two for the book, of contemporary works, illustrating the landscape I describe – Philip’s idea. He also suggested “interventions” into the book itself, to present alternative points of view, Márton’s and my dialogue being one. He additionally suggested I select works to add visual materials within the book. I soon agreed seeing the wisdom of such an approach. An overview is available associated with 14 visual text works in Oddity 18. (20)

As a totality, my writings on visual poetry and text art, and my gatherings of this work, are intended to promote an egalitarian, healthy visual poetry community fully integrated with other visual text arts. I have one voice among many, some agree and others not. It is in the hands of the group to decide whether or not to follow the inclusive model of correspondence/mail art or become a collection of ghettoes and dead end cul-de-sacs in conflict resulting in limited audience that Karl Young warned against in 1995.

A final note. One of the drives of the Stieglitz Circle before WWI was to manifest an American vision. While they were trying to accomplish something uniquely American, such a vision was already nascent in New Mexico. From the 1920s into the 1940s some of the Circle witnessed it but seemed not to recognize its importance. In the mid to late 1920s others saw it and were influenced before, during, and after they formed the Transcendental Group, 1938-1942. It was the development of the First Nation’s iconographic painting. And surely it is the First People that we should acknowledge first of all…? (21)

Navajo Prayer — Beauty Way

In beauty may I walk

All day long may I walk

Through the returning seasons may I walk

Beautifully I will possess again

Beautifully birds

Beautifully joyful birds

On the trail marked with pollen may I walk

With grasshoppers about my feet may I walk

With dew about my feet may I walk

With beauty may I walk

With beauty before me may I walk

With beauty behind me may I walk

With beauty above me may I walk

With beauty all around me may I walk

In old age, wandering on a trail of beauty,

lively, may I walk

In old age, wandering on a trail of beauty,

living again, may I walk

It is finished in beauty

It is finished in beauty.

Essay: karl kempton, Oceano, California. August, 2019

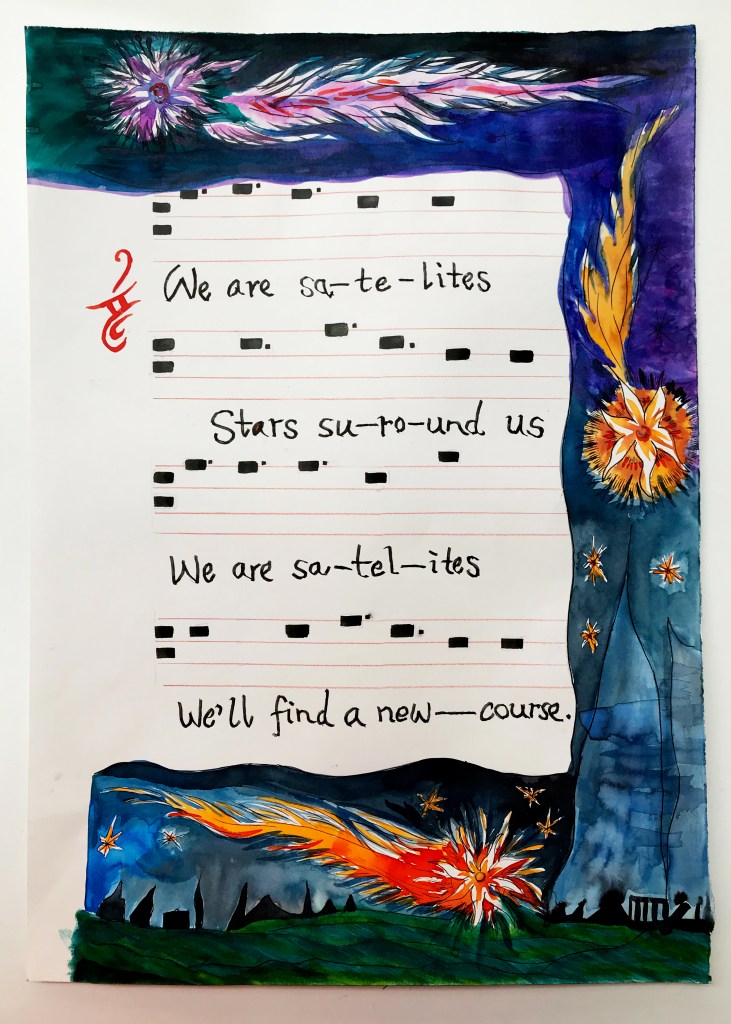

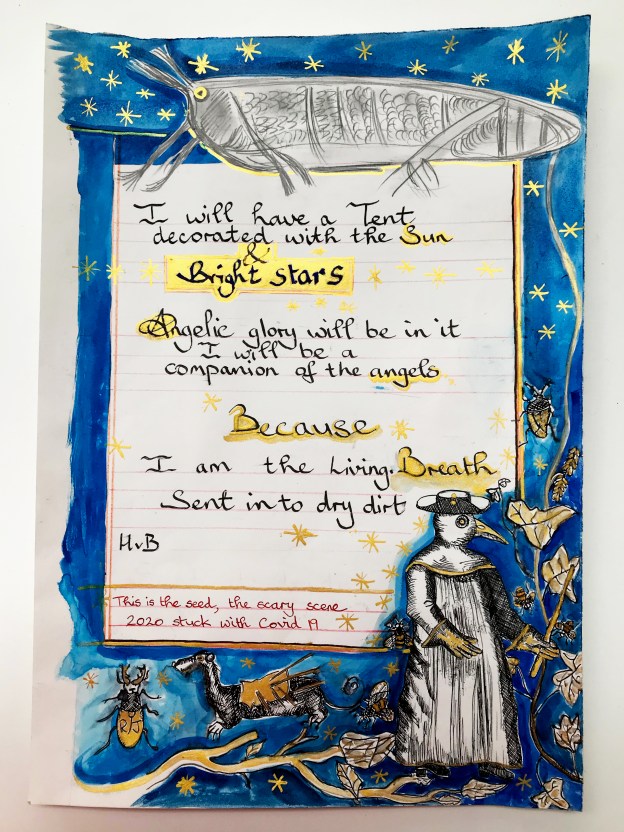

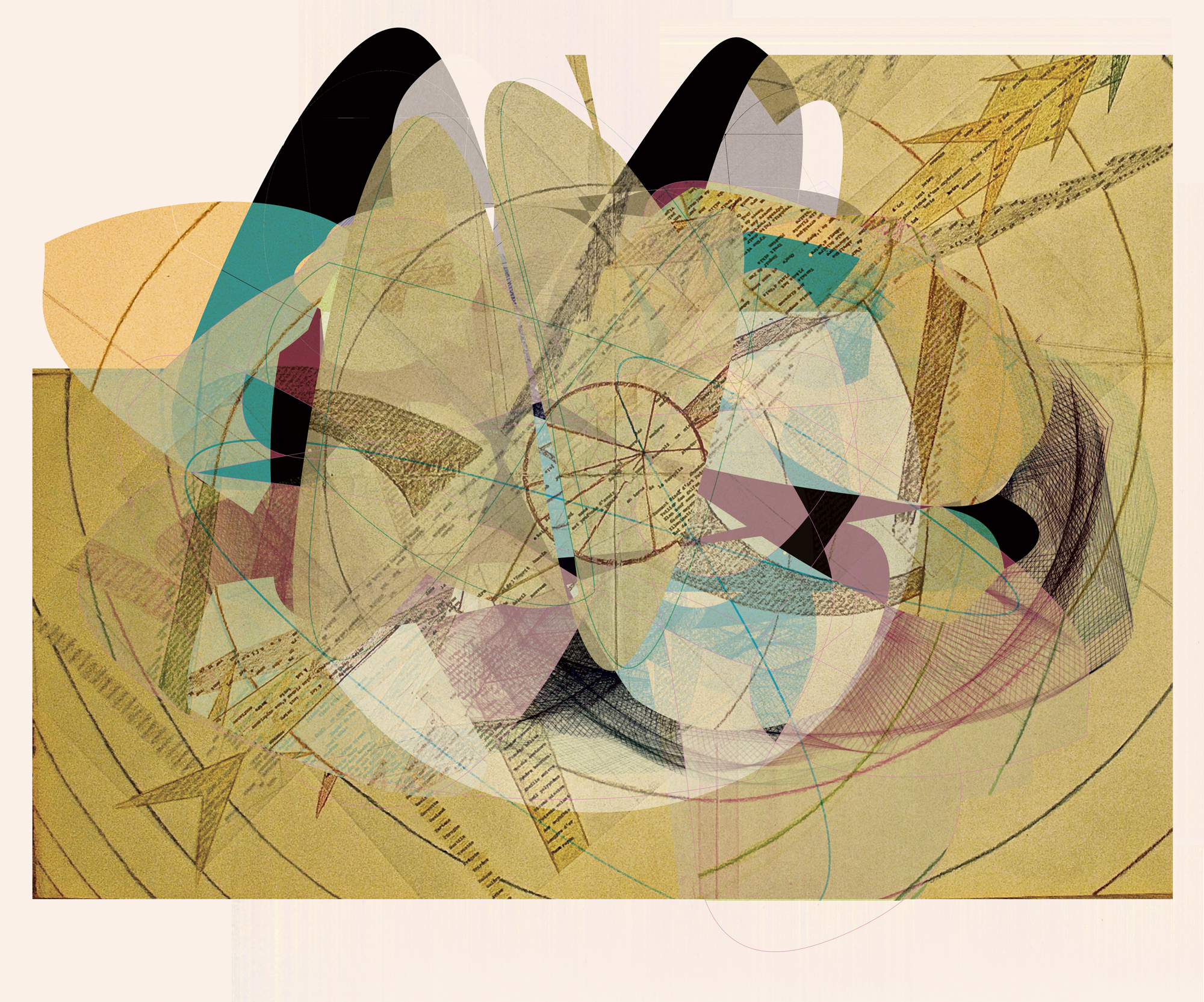

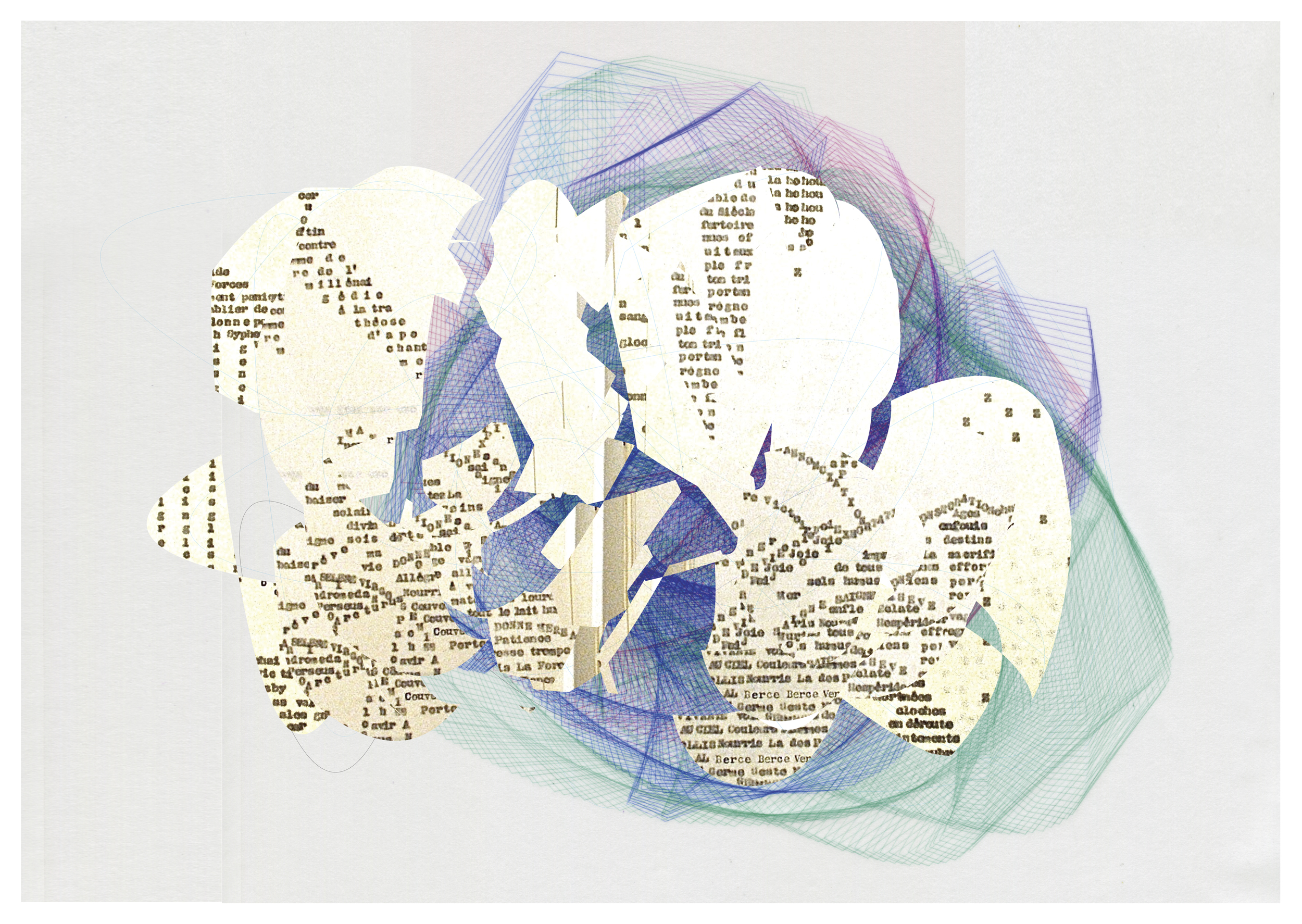

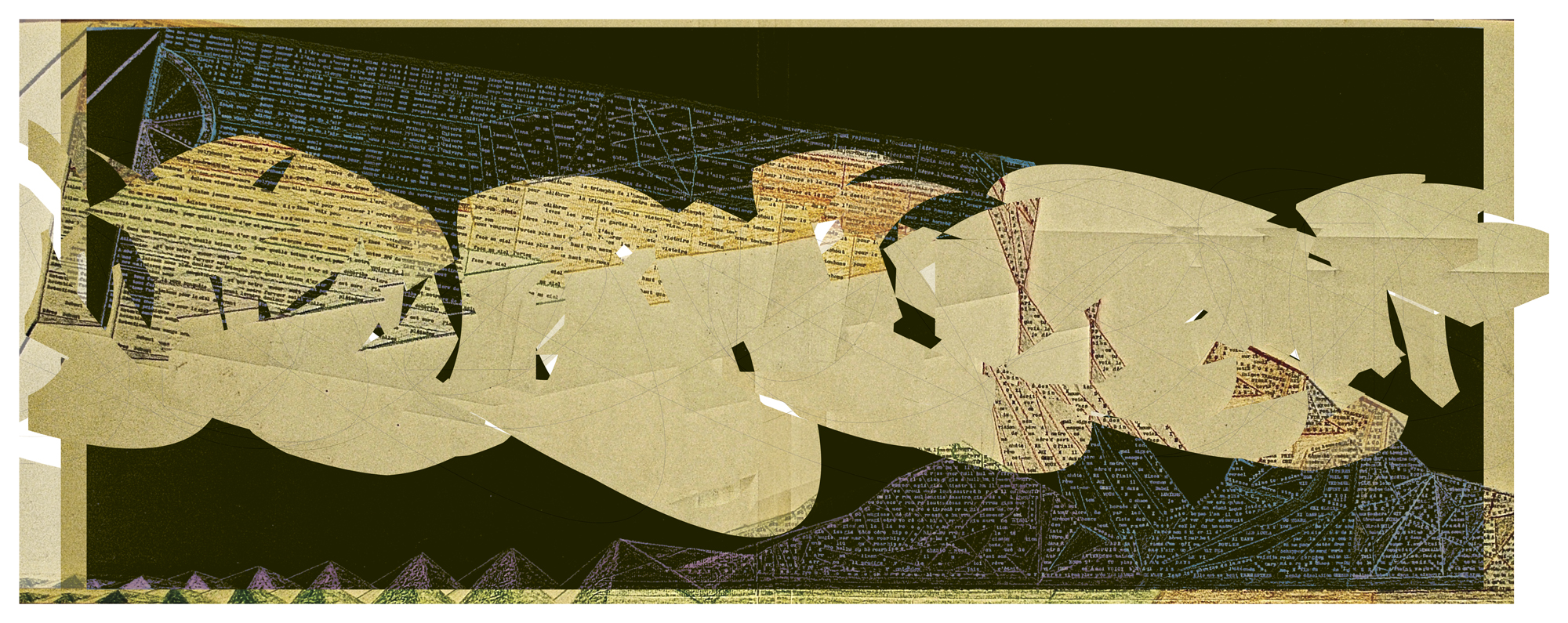

Visual text sequence by Mohammad Arif Khan, from the series Mystic Letter

FREE PDF DOWNLOAD OF A HISTORY OF VISUAL TEXT ART

Footnotes

1 http://www.logolalia.com/minimalistconcretepoetry/archives/cat_kempton_karl.html

2 http://visualpoetryrenegade.blogspot.com/

3 An intervention from Márton Koppány: “I’m especially glad to see Karl Young mentioned. It is important to keep his work alive. Based on my exchange of ideas and collaboration with him (which went on for one and a half decade or so), I feel that his knowledge, taste and inclinations were catholic. He was as open toward pre-modernist traditions and source-works (in Europe, Asia /with a special emphasis on Japan, because of his personal connections and also because of the shock of Hiroshima/, the Americas and elsewhere) as toward existentialism or the French Nouveau Roman, for instance. And all those sources influenced his poetry.”

4 http://www.thing.net/~grist/ld/bot/boturini.htm & http://www.thing.net/~grist/ld/bot/ky-anm.htm

5 http://www.thing.net/~grist/ld/japan/kitasono.htm

6 http://www.thing.net/~grist/l&d/kempatch.htm

7 Cross: http://synaptry.blogspot.com/2018/11/doris-cross.html, http://www.thing.net/~grist/l&d/dcross00.htm; Danon: http://synaptry.blogspot.com/2018/10/betty-da-

8 Rosenberg: http://synaptry.blogspot.com/2018/10/marilyn-r-rosen-

9 Anti-nuclear power, protecting sacred Chumash sites, fighting pesticide drift and use, and nearshore and offshore ocean environment protection.

10 They embraced the Brazilian Noigandres Group concrete poetry as heroic, despite the fact that none of the Noigandres Group were troubled by the fascist regime whilst it was in power, contrary to the experience of other Brazilian poets and visual poets arrested and tortured. None of the Noigandres members were jailed as they were apparently deemed safe, if not supporters of the status quo, i.e., not avant-garde but retro-garde? Think: stories of Clemente Padin’s and Jorge Caraballo’s incarcerations for several years under Uruguay’s military dictatorship, the jailing of Paulo Brusky (three times) and Daniel Santiago in Brazil, the kidnapping of Jesus Romero Galdamez Escobar by the El Salvadorian military, and the exiling of Guillermo Deisler from Chile. Perhaps these others were actually the heroic poets, visual and lexical…? Chile: how can we forget the poets, writers, artists and countless other citizens killed, tortured, or exiled?

From Polkinhorn’s paper, “Hyperotics: A Towards A Theory Of Experimental Poetry,” delivered at Yale’s “Symphosophia: The End of Literature”: “There are big stakes to continuing these arguments. Among them are the chance to define cultural history, not to mention more mundane consequences such as ten-ured university positions with full health, vision, and dental coverage as well as the possibility of retiring without sliding into poverty. So assertions about what is and is not experimental poetry (or some other cultural form) will continue, and as usual the primary beneficiaries of these discussions will continue to be the arguers, not those about whose works the arguments are being conducted.”

11 From Polkinhorn email: “One of the de Campos brothers was there, with his son, and he walked out of my presentation, in a grossly conspicuous fashion.” And: “The whole conference at Yale was a kind of set-up, a glorification arranged by the Language School manipulators to further their narrow agenda by getting the im-primatur of Yale for the Brazilian Concretists (and themselves of course). I crashed their party with the Menezes book.” Polkinhorn email exchange.

12 http://www.logolalia.com/minimalistconcretepoetry/

13 http://www.logolalia.com/minimalistconcretepoetry/archives/cat_kempton_karl.html

14 http://www.thing.net/~grist/l&d/kaldron.htm

15 http://www.thing.net/~grist/l&d/kal-note.htm

16 He created simultaneity, although it is often credited to Apollinaire and Marinetti. They reduced it to a single page; Barzun contended that a single voiced point of view poem in the new urban complexity was inadequate; it required multi voices simultaneously, choir-like poetry. His visual poems were also, in a sense, multi-voiced scores.

17 For English language roots, see White Goddess by Robert Graves.

18 Not to be confused with the religious, though in a few cases they are intertwined among individuals such as Robert Lax

19 https://www.pinterest.com/karlkempton/word-painting-1/

20 https://theoddmagazine.wixsite.com/oddity18 visual poetry issue: https://theoddmaga-

21 See the extraordinary anthology: Technicians of the Sacred: A Range of Poetries from Africa, America, Asia, Europe, and Oceania. Edited and with commentaries by Jerome Rothenberg. University of California Press; 3rd edition (2017) recommended.