Guest Blogger No 11

Three layers

by

Marco Giovenale

In 2011 I took part in the Bury Text Festival thanks to Tony Trehy’s invitation: he appreciated some “asemic sibyls” I had sent him.

I thought my participation could be structured and divided into three parts or levels/layers (again, thanks to Tony who welcomed them): a reading, a ‘performance’ (I’d rather say ‘installance’), and the presence of the two selected asemic sibyls on the black wall in the Wonder Room.

First layer.

The reading I gave offered a series of strange twisted prose pieces, some of them previously unpublished, some dispersed in magazines and chapbooks. The texts tried to mix and put together several paths of experiments: first of all the kind of mood one can find in Jean-Marie Gleize’s “prose en prose” (prose in prose, which evidently is not “poèmes en prose”, poetic prose & so on), then some post-langpo & flarf fragments.

One (already published) text was “CDK”, hosted by Drew Kunz in his Tir Aux Pigeons series. The pdf can still be found on line (here, for example: http://issuu.com/poesia2.0/docs/cdk). Another one was “log/log”, later published in http://wee-image.blogspot.com/2011/08/log-log-by-mgiovenale.html. (It was a text I had written at first for a chapbook series run by Susana Gardner, then I transformed and ‘compressed’ it, making it have its gravity center in a sentence I owe to Rachel Defay-Liautard: “meaning is everywhere” ––as a scaring observation).

All the texts I write are not thought and made to be performed, and they’re not meant to give shape to a classical “reading” (even if they have been and are actually read). They’re conceived to be “installed”. I often think the practice of installation is actually opposed (even if not enemy) to that of performance. (Some naive notes I once made remarked that performance is a sort of living sculpture where the voice just works on soundwaves; while an installation is a still and silent language object, separated from any scene and sound).

This opposition can be defined a weak one, if one considers ––also–– the

Second layer.

The people at the Bury Text Festival, on April 30th, were in fact surrounded (and unaware of being surrounded) by ‘installances’ I had made. The word “installance” comes from the two words “installation”+”performance”, and means that one (=I) decided to make some sort of secretly performed installation, leaving ––here and there and in hidden places everywhere in the rooms of the Text Festival–– very little pieces of paper & leaflets covered with asemic writing: they were in many corners, abandoned, forgotten, just …illegible unannounced sibyls lost in space, scattered messages almost hard to be found. (And: when found, impossible to be read). Another way to defy and deplete the ubiquitous meaning. (And: yes: a ‘meaningful’ strategy after all).

At the same time, two other (and ‘major’, and bigger) sibyls were hanging on the black wall: they formed the

Third layer.

Penny Anderson Guest Blogger No 10

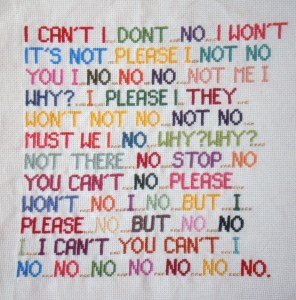

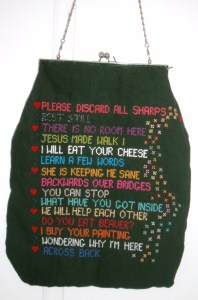

The Words were too much. Too many words. Even so, the words are not enough.

I was using my words as a post-grad at ‘The Art School Which Will Be Nameless.’ I was accepted there because of equivalent experience, that is, because of my words. I have written about: music, buildings, and how people live in buildings.

The experts at TASWWBN repeatedly requested a ‘visual response’ to our research. I said: ‘But you know I am a writer.’ They said: ‘So are we. And where’s your visual response?’

I said, my eyes are dim, I cannot see, as I am partially sighted.

And so, I began to sew. I stitched the words I noticed. I stitched the words I saw on walls, on tables, or outside. I also sewed the words I heard.

I told longer stories, using just a few words, I told of how I had travelled, how I lived, and where. Some people noticed my sewn words. They liked the words I sewed. I wrote about the buildings and the music, and I also wrote stories, which a kind man published so other people could read them.

I began to paint and draw letters, words and sentences, snippets of longer stories, using fewer words than I had previously considered essential. Again, some people liked this more than the larger concentrations of words (the words I am paid to write) which fed my ego, or rather my confidence. I now prefer sewing words, so that is what I do. There were special buildings, different longer buildings, to smaller precise, concentrated, colourful words. Tony Trehy curates the work in on such larger building, Bury Art Museum. He shows the words I sew at The Text Festival. Thank you Tony.

Guest blogger number 9 – Rachel Defay-Liautard

October 2010,

Tale] Context is

Geof Huth network about the Text Festival.

Being magneticfideally attracted to the Bury GROUNDed-series’ boundary-BREAKING content.

Encouraging mail exchanges with Geof Huth…

… leading to…

… encouraging mail exchanges with Tony Trehy.

March_April 2011,

dreams of ? Being

Submitting pieces (chiropractically conceived) to Geof Huth’ InterNaPwoWriMo

& Tony Trehy ‘ Wonder Room.

Amazeful gratituded. And grattitude too.

Amagazement.

> First of the two pieces selected for the Wonder Room:

R.A.S., la nuit, les étoiles. C’est trop petit chez

> Second of the two pieces selected for the Wonder Room:

Viewmorwindows, viewmorwindowtis, f.

April_May 2011,

-based stuff, similar

Friendly accompanied Bury travelogue.

Meeting wonder-poets, -artists, -durationfriends and –performers

in some partycularli well-timed and place.

, Barney, Eduard Escoffet, Geof Huth, Helen White, Marco Giovenale,

, Márton Koppány, Satu Kaikkonen, Steve Giasson,

, Tony Trehy,

Later attending Urschwittersonatly seminaturntablings. ((discretively.

End, then, subtlpying Warth Mill basement candidle VO/Xx-s.

April 5 2013,

al/experimental writing

Family accompanied London travelog.

Philip Davenport edition: The Dark Would language art anthology.

Attending Whitechapel Gallery launch, larch, larch, laterallhypnotized.

And (shy.

A withT.T.y conversation onward occuprogressing a performance idea for next Text Fest.

April_May_June 2014,

grammed looms and

Non accompanied Bury travel.

Inter and actively performing CONVERSE: all star.

The Text Festichivalresurrects in Galatée, Márton-reviewed. GALATEA RESURRECTS 22

May 2014 (bis),

compatible and w

Inthemorning justamazing Juxtavoices.

Meecheerfully cheermeetings.

Ron Silliman& Jörg Piringer& Eran Hadas&

Derek Beaulieu& Philip Davenport&

Sarah Sanders&

Projecting futurátions in Márton Koppány laborcompány.

August_October 2015,

other contributors. The

TOTAL RECALL at Bury Art Museum.

derek beaulieu and Philip Davenport curators for TT 20th curating anniversarty.

Ideally, the series made after Tom Knight’s Symbolics space-cadet keyboard was designed to be

randomly displayed among and as close as possible to other poets’ contributions,

so that none of the anabol is [ ] series separate pieces would show juxtaposed to each other.

> 1 out of 10 from the

anabol is [ ] series:

Current 2015,

Archive as a

Preparing a new performance eagerly lookwaiting for and wards Text Festival next occurrence.

Restoring a text-clothing element from CONVERSE: all star:

> The embroidomized cusT-shirt soon-to-be-integrated in Bury Art Archive:

+ Brainstorworking on a planned solo exhibition in Bury Art Gallery forthcoming 2017…

Guest blogger number 8 – Carolyn Thompson

In her guest blog Carolyn has used a series of quotes from novels, arranging them into a non linear text which reflects some of the thought processes behind her work, the way it is made and what compels her to make it.

When she came to write her story, she would wonder exactly when the books and the words started not just to mean something, but everything. […] Perhaps there would never be a precise answer as to when and where it occurred. In any case that’s getting ahead of myself. [Zusak, The Book Thief]

I would like to believe this is a story I’m telling. I need to believe it. I must believe it. Those who can believe that such stories are only stories have a better chance. If it’s a story I’m telling, then I have control over the ending. Then there will be an ending, to the story, and real life will come after it. […] But if it’s a story, even in my head, I must be telling it to someone. You don’t tell a story only to yourself. There’s always someone else. Even when there is no one. [Atwood, The Handmaid’s Tale]

We were the people who were not in the papers. We lived in the blank white spaces at the edges of print. It gave us more freedom. We lived in the gaps between the stories [Atwood, The Handmaid’s Tale]

The dances and the garden parties, the countless bottles of Scotch [Ballard, Empire of the Sun]

It’s an oasis of the forbidden [Atwood, The Handmaid’s Tale]

Better to reign in Hell, than serve in Heav’n. [Milton, Paradise Lost]

Persecution is good for you. [Cottrell Boyce, Millions]

Books everywhere! Each wall was armed with overcrowded yet immaculate shelving. It was barely possible to seethe paintwork. There were all different styles and sizes of lettering on the spines of the black, the red, the grey, the every-coloured books. It was one of the most beautiful things… [Zusak, The Book Thief]

It ever presents itself to my imagination as the region of beauty and delight [Shelley, Frankenstein]

She could smell the pages. She could almost taste the words as they stacked up around her. [Zusak, The Book Thief]

There is something at work in my soul, which I do not understand [Shelley, Frankenstein]

I begin with writing the first sentence—and trusting to Almighty God for the second. [Sterne, The Life & Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman]

What I must present is a made thing, not something born. [Atwood, The Handmaid’s Tale]

I sit in the chair and think about the word chair. It can also mean the leader of a meeting. It can also mean a mode of execution. It is the first syllable in charity. It is the French word for flesh. None of these facts has any connection with the others. These are the kinds of litanies I use [Atwood, The Handmaid’s Tale]

Every record has been destroyed or falsified, every book has been re-written, every picture has been re-painted, every statue and street and building has been re-named, every date has been altered. And that process is continuing day by day and minute by minute. [Orwell, Nineteen Eighty-Four]

Change, we were sure, was for the better always. We were revisionists [Atwood, The Handmaid’s Tale]

Shall we for ever make new books, as apothecaries make new mixtures, by pouring only out of one vessel into another? [Sterne, The Life & Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman]

…there is another view of the world out there and other eyes to see it and that’s where this is going [McCarthy, No Country for Old Men]

The simple transition from intention to action seemed an unimaginable miracle [Nabokov, Mary]

There is a love for the marvellous, a belief in the marvellous, intertwined in all my projects [Shelley, Frankenstein]

Do I not deserve to accomplish some great purpose? [Shelley, Frankenstein]

I was being excellent in a different, less obvious way [Cotttrell Boyce, Millions]

Yes, an illustrious career. I should hasten to admit, however that there was a considerable hiatus between the first stolen book and the second. [Zusak, The Book Thief]

I wish this story were different. I wish it were more civilized. I wish it showed me in a better light, if not happier, then at least more active, less hesitant, less distracted by trivia. I wish it had more shape. I wish it were about love, or about sudden realizations important to one’s life, or even about sunsets, birds, rainstorms, or snow. Maybe it is about those things, in a sense; but in the meantime there is so much else getting in the way, […] so many unsaid words [Atwood, The Handmaid’s Tale]

By telling you anything at all I’m at least believing in you. I believe you’re there, I believe you into being. Because I’m telling you this story I will your existence. I tell, therefore you are. [Atwood, The Handmaid’s Tale]

Maybe I’m crazy and this is some new kind of therapy. I wish it were true; then I could get better and this would go away. [Atwood, The Handmaid’s Tale]

Context is all. [Atwood, The Handmaid’s Tale]

Guest Blogger no 7 – Liz Collini

It can take a while to understand what you are doing when you make art. It is equally important not to understand it entirely. Intent is a funny thing; you start in one place thinking you know where you are headed, but you may end up somewhere completely unexpected. Things you put out into the world with the confidence of your initial intentions might not be received in the way you expected.

One of the great joys of the text festivals is that labels are irrelevant. Nobody cares if you are a visual artist, a poet, a musician or a performer. So while the web and social media seem to have decided that I am a typographer inventing a new font (I’m not), the festivals aren’t interested in those things. They accept the works on their own terms, giving them room to breathe, while at the same time establishing conversations between different works being shown or performed by other contributors.

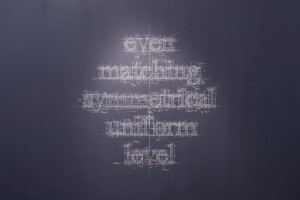

The festivals’ curators take risks and embrace the unexpected. They have given me generous spaces to make two large temporary wall drawings at two of the recent events. ‘Versions’, made in 2009 took a week to draw, and the installation itself became a sort of performance. Tony, Phil and Kat initially accepted the work completely on trust, as they had no real idea what would come out at the other end, nor, to a large degree, did I.

I Iove the picture of its erasure a few weeks later, partly because you can see the physicality involved, partly because it shows its impermanence, and partly because I wasn’t there to witness its demise.

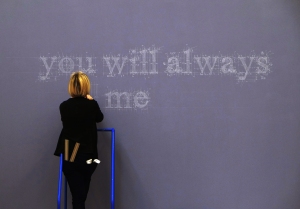

I worked in similar way in 2014, with the drawing ‘Construction V’, made during the opening weekend of the festival. The phrase eventually read

you will always

find me wanting

As the phrase emerged slowly over the weekend, there was a growing expectation of something romantic: apologies to those who hoped for an expression of love. But this phrase reflects an essential part of what is going on when I make work (in so far as I am aware of it, of course). It will never be perfect. It may be judged, and I anxiously try to forestall this with little handwritten notes annotating the Times New Roman letters with all their tradition and authority. Those two rulers in my back pocket do look like some sort of subliminal sign.

At present I am making new works on paper using liquid inks, handwriting and occasional figurative drawing, remembering the visceral pleasure of using my first fountain pen at primary school when we learned joined-up writing (Osmiroid, italic nib, green marbled body). The work takes as its starting point another set of memories derived from the film Camille. I was probably about six when saw Garbo in Camille on the television. A trace of this film lodged deep in my psyche, a memory of flowery whiteness, of fragrance, of delicacy and fragility, a ‘filminess’, something to do with glass. Although I clearly wouldn’t have had the words for it then, perhaps I sensed that death was being portrayed as transfiguring and close to the sublime.

Recently I made the connection between these memories and the plants in peoples’ front gardens – those with yellowing leaves and a mixture of red and dead brown flowers – these were actually camellias. They bear no relation to the blooms of my imagination constructed in the wake of the film. Perhaps I had confused them with gardenias. I can’t reconcile the gap between my imagined flower and the reality on a British street.

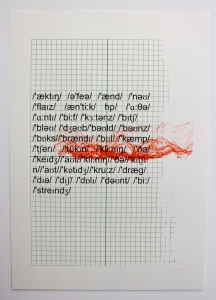

I have now read the novel on which the film was based (La dame aux camélias) and watched the 1930s film Camille again. My memory had clearly been layering and refracting to create what ‘it’ (or I) desired. The film is in some ways quite grotesque to 21st century eyes, even funny at times, and the final death scene was nothing like I remembered*. Dumas’ 1852 novel swings between melodrama and realism, and is morally ambivalent (there’s a lot of academic writing about this). There is a surprising frankness about prostitution and disease, including a ghastly exhumation scene, not surprisingly omitted from the film. Neither book nor film is anything like the memories I had of Camille. But, through revisiting the film and researching the novel and the camellia flower itself, I am discovering a whole new mass of stuff – language material – and that is what is taxing me now. The complex and strict systems and laws of plant naming are new to me and provoke questions about power and the drive to list, classify, differentiate and label (see the beginning of this piece). However esoteric, this botanical world is also quite intimidating and contrasts with the delicacy and fragility of flowers in the collective imagination. The very names of the varieties of camellia are incredible in themselves (a simple list has been the basis of a couple of recent works). On the one hand there are forces pressing towards grouping things on the basis of their similarities, on the other there are those that push apart in order to distinguish, split and separate. These countervailing forces are also political and cultural, extending way beyond the botanical.

So I am presently caught up in a storm of conflations – of a misremembered flower and a misremembered film, and of a whole system of classification with the potential for standing in for many other things, with text, image and a lot of ink. I have no idea what will come out at the other end, if anything at all, and that is part of the normal ups and downs of making new work.

*A co-incidence was seeing Marlene Dumas’ painting of Camille at the recent Tate Modern exhibition.

Guest blogger no 6 – Márton Koppány:

The Other Side

1.

If many decades ago my only book in Hungarian had been ridiculed by my own editor because of the three blank pages following each other, and as a consequence I had tried to get rid of my Hungarian and find other tools and means for communication, and had not met Bob Grumman, it would have sufficed me!

If I had gotten in touch with Bob Grumman, one of the most innocent souls and self-ironic minds I’ve ever met, and he had not talked to Geof Huth about me, and I had not gotten the support and friendship of both of them in moments when I was down (as usual) (but happy notwithstanding as usual) (as all of us), it would have sufficed me!

If I had gotten their support and Geof (it was him, I guess) had not mentioned my name to Tony Trehy, it would have sufficed me!

If he had talked to Tony about me, and Tony had come to Budapest and visited me, my wife and our dog-companion, Gertrude, and had taken with him an old copy of The Other Side, and he had liked Gertrude a lot, and had disliked The Other Side, it would have sufficed me!

If he had liked The Other Side almost as much as he liked Gertrude and had not invited me to the next Text Festival in 2011, it would have sufficed me!

If he had invited me to the Text Festival of 2011 and invited me to the party in his and Sue’s apartment where I met many wonderful digital friends in flesh for the first time, and tasted Sue’s wonderful potato-based stuff, similar to Hungarian rakott krumpli (and a lot of other marvels), and Stephen Nelson and I had not gotten drunk a bit, and had not tried to approach, very slowly and carefully what was left of the dip, with minimalist crumbs of tortilla chips in hands, and we had not cried of laughter (poetry at its best!), it would have sufficed me!

If we had cried of laughter and I had the opportunity to walk Barney the next morning and be included in readings and exhibits, and see Bury, and be miraculously involved in activities similar to those which make me isolated in those days which are not different, and had not listened to Jaap Blonk performing a part of the Ursonate, one of the most cathartic events I’ve ever witnessed, it would have sufficed me!

If I had listened to Jaap Blonk and had not discovered The Secret, my only poem ever (because the only one known by the larger public, I guess) hidden by Philip Davenport, very appropriately, in a cattle truck, it would have sufficed me!

If Phil had exhibited The Secret (my only poem) by hiding it in the Bury Transport Museum, and hadn’t published it as the cover art for The Dark Would, and the book hadn’t segued into events related to the next Text Festival as well, it would have sufficed me!

If Phil had published The Secret and I had been invited to the next Text Festival in 2014 as well, and had seen strikingly beautiful and/or funny works again by Matt Dalby, Caroline Bergvall, Liz Collini, Steve Giasson, Sarah Sanders and others, and I had not gotten lost in the company of Eran Hadas and Jörg Piringer, because the taxi driver was the reincarnation of the East-German taxi driver in Jim Jarmush’s Night on Earth, and we hadn’t cried of laughter (the best kind of poetry!), it would have sufficed me!

If we had gotten lost, and Tony hadn’t exhibited The Other Side, it would have sufficed me!

If Tony had exhibited The Other Side, and I had never reached It, it would have sufficed me!

2.

A few years ago I started translating my visual poems into verbal descriptions. The idea had come from questions by friends and my questions to them about this or that (mostly technical) detail in my works. Then it became a small game, and I started using those descriptions in themselves, changing them into monologues, and without the original pieces. I had the opportunity of reading a set of them at the 2011 Text Festival too. What I especially enjoyed about the two Text Festivals I’ve participated in was their equal trust in and scepticism about words and images and everything between and beyond: text as image as text as…

I find your making a connection between mail art and national symbols through my stamps intriguing. I’ve never thought about it, but you are right, they must correspond. Both are about being (or feeling to be) an outsider, in the first case in the arts, in the second case as a bad citizen who doesn’t belong to the “folk”. The guy should leave now, because we see on the first stamp that it is only one minute to midnight. But on the other stamp the escape of the trunkless foot is quite artificial – almost ceremonial. It belongs to the scene. We are in a stamp, after all.

Márton Koppány

Budapest, 20/08/2015

Jez Dolan our next guest blogger talks about chance meetings and where they can lead…….

Bona to vada your dolly old eek!

A chance meeting with Bury Art Museum director Tony Trehy over lunch at the 2012 Liverpool Biennial lead to the next step in the Polari Mission. Our paths had crossed (in a previous life) through my work as a local authority arts officer many years before. Giving TT a whistle stop tour through my transformation into full-time artist, and my (then) current work with Polari, TT said “You have to bring it to Bury”.

Polari, or ‘the lost language of Gay men’, a sociolect – more than a slang but less than a language, used chiefly by gay men, and active in England primarily between the 1920’s and 1970’s but with a longer, hidden, and more complex history and etymology, Polari is at once both disguise and identifier.

Polari is a spoken rather than a written phenomenon. When looking to exhibit artefacts or objects, little exists, but in an attempt to link the idea of ‘the archive’, and specifically Bury’s Text Art Archive to Polari we developed the idea of ‘personal archiving’ – each of us has our own archive – a shoebox under the bed, tea chests in the attic, or something more documented and catalogued. How do the objects we choose to keep tell our stories, and, in the case of people who identify as LGBT, specifically the coming out story? A story, which we repeat and reconstruct over years.

My use of text in my practice had happened almost accidentally. I made a project in 2012 entitled ‘Tributes’, which took the traditional UK floral funeral tribute, usually saying ‘MUM’, ‘GRAN’ or similar, and adapted the format to depict homophobic abuse words in photographic portraits. As part of this project I started to work with screen printing, using photographs of the decaying flowers and combining these almost sculptural forms with texts which in some way reflected the word ‘tribute’.

Working with Museum curator Susan Lord, we chose to install a massive blackboard in the museum case spanning an entire wall, and made a chalk drawing which combined Polari texts, phrases, snatches of conversation, even lyrics from a Morrisey song (Piccadilly Palare). The chalk board combined ideas of lessons, how we could teach people something about Polari, but more significantly, Polari as a palimpsest, as disappearing, as fragile and endangered.

The theme of the central exhibition of the Text Festival was ‘The Language of Lists’, so I took this opportunity to create new works specifically for the festival exploring this idea. Polari emerges from a wide variety of language sources: Yiddish, Italian, Thieves Cant, Parlari (fairground & circus language), and many others. I produced a number of screen prints, which reflected the languages of origin of Polari words. In a further reflection of the Text Festival, I utilised cut – up methods from which to create a new language of lists for each new pieces.

So a list of words of Yiddish origin were combined with a menorah, and the text of a Hebrew psalm, a list of Parlari words were combined with the figure of Punch, and so on. We made further links with the Bury Museum collection with the inclusion of objects, including the crocodile (complete with sequins) from a Punch & Judy set, an Eighteenth Century sailors good luck charm, and a pair of size eight red stilettos.

Polari’s performative nature had previously led to the creation of ‘The Polari Mission Bibleathon’, a durational performance work which took the World’s only extant copy of The Polari Bible (King James version), and something we revisited for Text Festival, where a select team of Polari scholars performed a selection of Bible readings in the Victorian splendour of Bury’s main gallery:

“The parkering ninty of kertever is carked it.”

The North West is incredibly lucky to have Bury Art Museum & Sculpture Centre, the Text Festival, and the Text Art Archive as a series of valuable resources and spaces in which great things can happen. Long may they continue to happen.

Jez Dolan

August 2015

Guest blogger number 4 is Tony Lopez long time collaborator of the Bury Text Festivals, in this piece Tony talks about his artworks and the various publications he has been involved in.

Tony Lopez

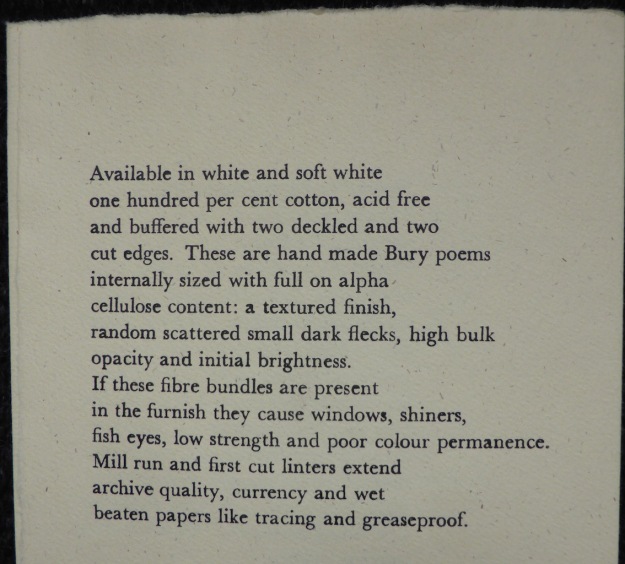

Working with Tony Trehy at the Bury Art Museum, I have managed to get some things made that wouldn’t have been possible otherwise. ‘Works on Paper’ was commissioned in 2008. I stayed in Manchester and spent a few days visiting Bury just finding out about the place, people and history, including the library and archive. Of course Bury is a prime site in the Industrial Revolution both in terms of technical innovation and its rapid economic development as a manufacturing centre. I was particularly interested in Bury’s later position in the early twentieth century as a world-leading producer of paper. This makes sense when you realise that industrial paper production came about as a kind of diversification of the cotton industry after much earlier breakthroughs in mechanical weaving, John Kay’s flying shuttle, programmed looms and so on. They had cotton waste and rags, water and then steam power; factories with highly trained mechanics and inventive engineers, and were very well placed to respond to the explosion of print culture.

So ‘Works on Paper’ is a poem that imagines and responds to that cultural knot and industrial complex. I began by searching for paper language used in technical description and also playing with the idea of language on paper, capturing history and ideas. The poem is a reflexive thing that attends to its own construction and tries on different forms and different kinds of information as it proceeds and processes text. It also uses the refrain ‘Bury Poems’ right through. I wanted it to be produced in a physical form that related to paper production but that was set aside for a while. I was invited to read at the Text Festival in 2009 with Carol Watts and Philip Davenport at an afternoon performance at the Met called The Bury Poems. This was the first presentation of that poem to an audience. Later Philip Davenport edited the book The Bury Poems (2011) with work by Robert Grenier, Ron Silliman, Geof Huth, Carol Watts, Philip Davenport, Holly Pester, Tony Trehy and my poem, which was broken up and distributed throughout the book, out of sequence, so it became something completely different. Phil did this in good faith I’m sure, I count him as a friend and I know he wouldn’t deliberately sabotage my work but I was astonished to find my poem cut up and remixed. The Bury Poems is an attractive book with lots of interesting writing and some fine photographic work, so it was a strange experience to have my poem included but garbled in this way. I was glad when there was an opportunity to publish the work separately and to establish the text as it was composed. Works on Paper was letterpress printed on 130 gsm Hahnemuhle old antique laid paper by Richard Parker and published in October 2011 by Crater Press, London and Brighton. It is a large format pamphlet made out of a single folded sheet of 100% cotton handmade paper and its physical form relates to the language and subject of the poem.

Tony Trehy came to visit me in Exmouth when he gave a reading at the Exeter Phoenix Arts Centre; I think that was in 2010. While he was here he told me about his plans for the third Text Festival that was planned for 2011. One of the three exhibitions he had in mind was a show that would be put together around Robert Grenier’s ground-breaking publication Sentences. Now Sentences was a primary and influential work for the USA language writers: a minimalist, anti-narrative poem consisting of 500 5 x 8 inch index cards each printed with a few words or phrases and packed in no special order in a clothbound box. Whale Cloth Press issued the original publication in 1978 and there is now a free online version that mimics the reading experience as much as possible by producing a different card order each time you view it. The texts on cards are various: beautiful, unexpected, minimal, cranky, obscure, obvious, daft, touching, comic – but they are not sentences.

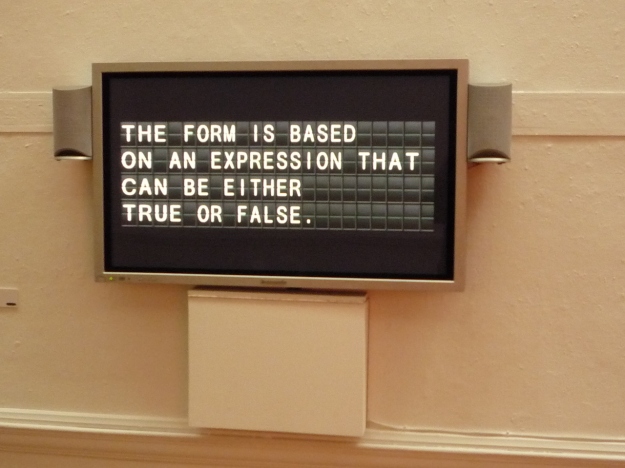

Tony’s plan was to show a copy of this work at the centre of a big room and to exhibit around it a number of more recent and contemporary pieces that related to Grenier’s Sentences. I thought that this was a great idea for a show and I had something already planned that would really work in that context. I had been collecting material for a large-scale book, taking individual sentences from a very wide variety of printed sources and composing by arranging this material into sections or chapters each of 100 sentences. I wanted to make a streamlined version using shorter sentences shown on an automated message display system. The piece was composed by selecting sentences from a much larger, really enormous set, establishing total discontinuity and a comedy in found material. I was keen to use a Solari departure board such as you would find in some airports and train stations. The noise and movement of the little revolving letter boards was an attractive aspect of presenting the text in this way, all the fleeting characters seen moving and then coming to a stop in stages as the message changed. We tried over the next few months to source a Solari departure board without any luck and I was wondering if the project was possible after all when a friend John Hall suggested that we try to animate the letters and work out if it could be done on film. Eventually his son Birdie (who works for an online content provider) suggested that it was just the kind of thing you could buy as a plug-in and there it was. My son Tom programmed my text into the flash animation and converted the flash into a movie on DVD. The technical staff at Bury boxed in a DVD player and speakers with a large screen monitor that looked really neat. The installation had a great impact in the gallery because it wasn’t moving all the time, and when it started up the noise drew the viewers’ attention to a change in the text.

By the time that the exhibition Sentences was shown in the Art Gallery the idea of using that Robert Grenier piece had been passed over (a much larger display of his more recent drawn poems had been shown in the Bury exhibition Irony of Flatness) but I was glad to have More and More, my first major work in text art go into a permanent collection and be shown in the exhibition alongside work by Joseph Beuys, Marcel Broodthaers, Pavel Buchler, Shezad Dawood, Helmut Herbst, Kate Pickering, Ron Silliman, Nick Thurston, George Widener and others. Since then More and More has been exhibited (on loan from Bury Art Museum) at the TR1 gallery, Tampere, Finland; The South Bank Centre, London; Arnolfini, Bristol; Egenis at Exeter University; and Whitechapel Gallery in London. Oh and I have been collaborating with Phil Davenport on a whole range of projects including his book The Dark Would (2013), his exhibition at Summerhall, Edinburgh, and my book The Text Festivals: Language Art and Material Poetry (2013).

Tony Lopez – July 2015

Our third guest blogger is artist Helen White, Helen discusses her commission for the 2011 Text Festival – ‘Soluble Colonies’.

Soluble Colonies at Bury Art Museum

Isn’t it something everyone dreams of? Being ushered through the locked door at the back of museum into the place where it keeps all its secrets? In Bury’s natural history archive, stuffed birds share the grey metal shelves with fossils and Victorian egg collections. A white cat with glass eyes peers into a cabinet of hawks. Some of the items were bewildering. A handful of pebbles, the kind I keep in my coat pocket? A donation, apparently. Stuffed birds of paradise, okay, but a stuffed pigeon? For creating atmosphere, curator Susan Lord explains: if you were making an educational display with a Victorian street scene, for example, you’d need pigeons. I was given special gloves, which I assumed were to protect delicate or precious exhibits from my grubbing fingers. Not so, according to Susan: it was more because taxidermists often used arsenic in their stuffing.

I had come to Bury to install my “soluble colonies,” a piece whose original habitat was waste ground and urban green spaces. They are colonies of little scraps of paper that grow and mutate around the word ‘is’, fading and changing as they age.

The installation was commissioned by Tony Trehy for the Text Festival in 2011. It was his idea to put the colonies in a glass case along with museum items. I was unsure at first: the colonies were feral, mortal, what would they do in dust-free suspended animation? Long before I did, Tony must have seen the parallels between the colonies and a museum’s activities of labelling, classifying, naming… colonising perhaps. I have never intended the colonies to properly label or classify anything, of course, but pretending to do so is half the fun of them.

The exhibits I fell most in love with were the humble ones, things too dilapidated or ordinary to attract visitors’ eyes. A bird’s head that had lost its body, stones and seashells, a moth-eaten chick, along with the birds of paradise, corals and excerpts from earlier works of my own.

Reflected in the glass cases, I discovered museum folded in on museum. There was the museum of things, the thrill of inviting forgotten objects to do a new, if dusty, dance. But then there was the living museum full of people: the “permanent collection” of curators and the “temporary exhibition” of artists who had come to Bury for the Text Festival. Actively working with curators, rather than just handing over a picture and asking them to hang it on the wall, as it were, was exciting and inspiring. Both Tony, as the Text Festival curator, and Susan as the curator in charge of the archive, contributed so much to the installation that I think of it as a collaborative piece, with Tony providing the inspiration to transfer it from the outdoors to the museum and Susan conjuring up ever more peculiar items.

When the Text Festival opened, I finally got to meet the other artists as well. Visual poets and other language artists tend to have far-flung networks of friends and peers around the world, but there are few opportunities to actually meet each other face to face. After years of enjoying their work, buying their books and reading their blogs, I was thrilled to find myself in the same room as “old friends” from Canada, Finland, Hungary and the US as well as meeting new people and discovering their work. In my mind the concept of a museum became more fluid and fleeting, moving from a collection of objects to a collection of people to a kaleidoscope of moments.

Both the “archive of people” and the items I chose from the archive of objects were brief configurations of more permanent wholes. In their glass case in Bury, the soluble colonies could not be as ephemeral as I intended them to be – as literally soluble – because there was no rain to dissolve the ink or dirt and dust to obscure the text. But I think they did retain their function as markers of temporary realities, momentary perspectives. Five years later, while writing this, I suddenly came across ‘The Blue Marble Project’ by Kristin Prevallet. Prevallet explains her need to mark the moment, a kind of guerrilla curatorship of the world around her:

“I’d like to think that marking monuments in the present is an exercise in observing how the genius of particulars – of seeing what one passes every day, what one takes for granted or even chooses not to observe – can connect us to our local environment. […] To make a passing thing monumental: this is an introverted activism that has no other effect than the movement of mind from one layer of perception to another: a sand bank in the middle of the road that tomorrow will be blown away by a truck’s exhaust, a brick on the verge of falling off a building which, in due time, will either fall or be fixed.” (from I’ll Drown My Book – Conceptual Writing by Women, ed. Caroline Bergvall et al, 2012, Les Figues Press, Los Angeles).

Beyond the glass case with all its heavy history – and its delicious potential for subversion and play – perhaps there is a ‘wild museum’, an archive of the ever-changing, sparkling passage of installations and visitors, memory and imagination, on either side of the glass. The opportunity to play with that point of balance during the Text Festival was a precious gift.

Helen White

June 2015

http://krikri.be/helen/colonies/colonies0.html

Our next guest blogger is Derek Beaulieu. Derek’s work has featured in two of Bury’s Texts Festivals; excitingly Derek is the 2014-16 Calgary Poet Laureate as well as the creator of no press. In this blog post he gives the background to no press and encourages all of us who have a desktop printer or access to a photocopier to begin producing our own work.

Since 2005 I have edited & published no press, a small press dedicated to publishing whatever the hell I feel like. No press has published over 270 different editions in the last 10 years – about 1 every two weeks – in editions of between 5 and 150 copies. Each edition is printed in my kitchen and folded, trimmed, stacked and sewn in my flat. My publishing mandate is idiosyncratic: I publish what I want to publish. The author receives ½ the copies as “payment” and the remainder are given away or sold at a (very) modest fee, usually only enough to barely recuperate the cost of material, but not the cost of my time. no press is a press of 1—just me—I publish work that I like, or that has me challenged, confused or bothered. no press has published fiction, poetry, essays, visual poetry, cartoons and sound poetry scores and performances (on CD). The mandate is defined loosely enough to allow it to reflect my reading and my community. Of the print that I don’t mail to the author – the remaining 50% – a very large section is handed out and donated. In my opinion, the small press gift economy is one that fosters good will within the community. We look to each other as our first readers, our first editors—with a sense of trust and generosity. I enjoy sharing discoveries I’ve made in my own reading, if I encounter a text which I think should be read, should be shared with a group of writers. I look to my printer, my needle & thread to take the time to present this manuscript in a way that compliments the time the author took in writing it. Ideally this is a conversation not a monologue.

Since my first involvement with Bury Art Museum’s Text Festival in 2011, I have donated a copy of every No Press publication to the Text Art Archive.

It is my aim that this donation will compliment the history of text-based artwork and radical/experimental writing in the UK.

My practice has been informed for years by the writing of dom sylvester houedard (who’s archives are at Manchester’s John Rylands Library), London’s Bob Cobbing (and his press Writers Forum), Ian Hamilton Findlay … not to mention contemporary work being published by York’s Information as Material press, the archives and collections at Shandy Hall, and small presses and authors through-out the north.

In my opinion writing is a public act, we must learn (even the most introverted of us) to share our work with a readership. See our work as worth sharing, our voices as worth hearing. It doesn’t have to be a huge public gesture; it could 10 copies among friends. Share.

There are a growing number of online print-on-demand publishers like Lulu and Blurb, and many photocopy shops will do collation and binding – but those are far from the only options. Anyone who has a desktop printer or access to a photocopier (or a typewriter, or a silkscreen or rubberstamp letters or any number of intriguing possibilities) can produce his/her own work. Paper, printer, stapler, scissors.

A challenge to my peers: publish your own work. Start a small press. Find the material that your colleagues are making that impresses you and publish it in pamphlets, in leaflets, in chapbooks and broadsides, posters and ephemera. It is all too easy to rely on other people to do the work for you – to allow the means of distribution to remain with book publishers, magazines and journals. Small press builds community through gifts and exchange, through consideration and generosity, through the creative interplay and dialogue with each other’s work. Small press publishing allows authors to present their work in a way that physically responds to the content – texture, size, shape, colour and binding all become aesthetic decisions that the author her/himself can shape. The internet is rife with instructions on how to hand bind books. Make stuff, hand it out, talk to people. The best advice I have is give ‘er.

Derek Beaulieu

30th May 2015

Trivia Press is 50 years old this year! In celebration I have asked Richard Pinkney its founder to be our very first guest blogger and write a little bit about how it all came about.

Trivia Press by Richard Pinkney

Trivia Press was conceived as a result of two early exhibitions I had in Edinburgh, the first at the embryonic Traverse Theatre in 1963 and then again at Jim Haynes’ Paperback Bookshop in 1965. I had printed a series of dry point engravings for the Traverse show and liked the notion of a number of associated works representing a narrative idea. Subsequently, among the pieces shown in the bookshop cellar, including 3D interactive items, were a number of drawings that included diagrammatic and typographic imagery. Both shows had at their kernel, tangible topics with little apparent consequence and processes with distinct outcomes and metaphorical potential.

By 1966, I was a member of a controversial Ground Course teaching team led by Roy Ascott at Ipswich Civic College, School of Art. In the air were cybernetics, multimedia, concrete poetry, happenings, auto-destructivism, silk-screen printing et al. So, using a notebook full of aphoristic texts, primitive poems constructed by random selection from “Times” ballet and opera reviews and fragments of imagined ideographs, I put together the first Trivia Press broadsheets. I distributed them widely by leaving individual copies in pubs, waiting rooms, on trains and posted them through promising letterboxes. It is probable that not many were read and even fewer have survived. Nonetheless, several more followed. On moving to London I found that Curwen Press quite liked selling them for two shillings and sixpence each and I was delighted when their huge business style cheque for one shilling and eight pence arrived as my share in each sale.

After the Ground Course team was broken up, a move to London resulted in introductions to Ian Tyson and Ron King and fruitful collaborations with them as Tetrad and Circle Presses got off the ground. However, I found the cynicism and pressure of metropolitan life very incompatible and wasted no time escaping from London back to Suffolk. However, I maintained contact with Ian and an involvement in Tetrad projects while continuing to teach at St. Martins School of Art. However, Ian’s notion of the Artist Book’s role was more market aware and sophisticated than my own intentions for Trivia Press.

By the end of the 70’s, I was no longer teaching and back in Suffolk I was involved in engineering and timber frame house design. Trivia Press was going through a constrained period but in the background, material needing a serial or narrative treatment from me was accumulating inexorably. Computers were becoming affordable and small-scale desktop publishing had become capable of delivering decent outcomes that were within the compass of an artist with modest ambitions. Lots of stuff that I had externalised into diaries and notebooks could be shared with a few other people, albeit in relatively small numbers. Once again, I found myself sitting-in on a shared exhibition at the Edinburgh Festival. I was, as usual, jotting ideas down in my notebook and conjecturing about simply produced black and white postcards and A5 packets that could be broadcast via the Mailart network and a slumbering Trivia Press offered a friendly format and a convivial context.

Trivia Press has subsequently and quietly enabled me to enjoy the creation of a platform of musings, insights, imponderables, silliness and moments of wit and complaint while confirming my idiosyncratic way of sharing my reflections and non-representation narratives with others.

Trivia Press is fifty years old in 2015. By way of celebration, its landmark offering will be a portfolio of ninety drawings and twenty-four coloured developments in six volumes with two appendices, published in an edition of twenty five signed, numbered and entitled Best foot forward.

Richard Pinkney

Further to 50 years of Trivia Press Richard Pinkney 16.05.15

In 2014, I reread Laurence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy and William Least Heat Moon’s River Horse. Both books invite one to consider the nature and coincidences of journeying and wandering.

My preoccupation over the last 50 years or so has been to employ non-representational and idiosyncratic styles to achieve narrative ends. When in the past I have been asked by students and others for direction, I have suggested that they abandon “the middle of the road” and set off “across the bracken”.

There is a deal of advice available suggesting what may be an optimum or acceptable route. However, intuition urges that exploring ephemeral experiences may reveal illuminating juxtapositions and stimulating conundrums. I admit to enjoying the apparently irrelevant or incongruent and undervaluing irrefutable answers. Working within a landscape (grid in my case) there are options of forward, back, various kinds of sideways and all sorts of ups and downs. So, in this group of works, here I go again!

“Best foot forward” started in a notebook as an ever-expanding series of jottings that I formalised on my computer. I reviewed the first ninety drawings and chose moments along the way to develop as one-stop recollections.

The outcome, as so often, was a matter of convenience becoming six sections of fifteen b&w drawings, four coloured ‘lay-bys’ and two appendices of six coloured images each that were prompted by the involvement of my grandchildren. The process is via a very basic graphics app, a home ink-jet printer and Somerset enhanced paper from St Cuthberts Mill.

pages from the Best foot forward notebook:

Pingback: Tony Lopez on his work for the Bury Text Festival | THE OTHER ROOM

Pingback: “three layers”, by mg, @ the text archive blog | slowforward