People who have experienced homelessness have collaborated to make a medieval-style illuminated manuscript, based upon The Book of Hours, describing their daily lives. Unbound pages from the book debuted at Bury Art Museum on May 18 2021, on show until mid-July 2021.

A BOOK OF OURS was handmade in Manchester, England 2019-21 by over 100 people with lived experience of homelessness, or at risk of homelessness. The project was devised and directed by poet Philip Davenport and visual artist Lois Blackburn, as arthur+martha. Significant events, celebrations, memorials document these hugely individual lives, in a large visual-poetic work by people who don’t appear in official histories. The project was supported by the Heritage Lottery Fund; workshops took place at The Booth Centre and Back on Track in Manchester.

1. “Ours”

O-U-R-S occupies H-O-U-R-S, just as P-O-E-T-R-Y occupies P-O-V-E-R-T-Y. In each case just one consonant (H, V) separates oppression from value, identity, and beauty. The book intervenes in an injustice. “The intent in our case is that this homeless history, this culture is iterated and has a place to arrive on a page, to be finally OURS” (Philip Davenport). Time for the homeless can be a steely clock marking deprivations and chaos, an imposition from without of relentless vulnerabilities to lack: lack of shelter, lack of health and health care, lack of stability and safety. The imagination learns to reinforce this trap of time. In the art room, organized as an arthur+martha event, the mind begins to free up…

“Mine” becomes “Ours”—what is possessed is voice, memory, reflection, wisdom of not the solitary individual but many persons brought together, who co-exist on the page and in the book; they possess the untold history of people with lived experience of homelessness.

2. Leaders of The Book of Ours Project

The ethics behind The Book of Ours and Homeless Library projects: “the story is theirs to tell.” How do the leaders of arthur+martha fulfill this remit when it is they who have planned, organized, and conducted, and participated in the lives and imaginations of people with the lived experience of homelessness? They come with various marks of visibility and power that a society based upon inequality confers on some but denies to others. Phil Davenport and Lois Blackburn, along with their colleague in music Matt Hill, acknowledge the privilege—with its access to workshop space, funding, and education—as they are vigilant about reducing to a minimum the temptations of appropriation and exploitation of the precarious vitality of other lives. They characterize their roles as “curators or midwives” (Matt Hill) of lives and works not their own. They are conservationists in the way that poets, from the beginning of recorded poetry, “conserve the image of a person across time” (Allen Grossman). They facilitate, rather than control and interpret, an event of living and shaping.

A man called J came into a music session and, listening to Matt’s guitar, asked if he could borrow it for a moment. A very good player, he began a striking melody, which Matt immediately recorded. Matt asked J to repeat it but he suddenly became shy. Matt nonetheless placed it as an undersong to “Killing Floor,” returning to the fragment throughout the song. J didn’t know where his melody came from: an unidentified shard of musical history saved from oblivion by Matt’s attentive and practiced ear, a disarming presence not interpreting but apprehending and conserving something of value. Commissioning becomes a form of collective artistic practice: I will do some of the work on your behalf . . , but, says Lois, “we are always checking where the power is,” making sure that noone’s authority gets usurped by another’s. To intervene or enhance often means to compensate for a severe handicap—most evident, the leaders come to their project with acquired training: when they see a blank page, they know how to begin filling it up, with language or with design. Without that experience, a person “comes [to the page] naked into the world,” terrified of a boundariless emptiness. The leaders give them boundaries, coordinates. The artist Lois draws a horizontal line, puts in an image, marks out a space for a text; the poet Phil lineates the poetic speech of a participant. Phil, Lois, and Matt, along with the other makers around the table, abolish the terror of creation in isolation.

Phil introduces the participants to Blake, Shelley, Hildegard of Bingen, and The Book of Hours, at which point he lets go. The books join the mayhem of pages on the worktable.

3. The Archaic and an Imperfect Fit

“Archaic” in this project stands for anything that grates against the idea of art as purity, consistency, and singularity of construction, which usually points to a principle of exclusion of unwanted materials and voices. “Imperfect fit” (1) characterizes art that deliberately fosters signs of what perfection would call a mistake or an inaccuracy but that in fact signifies inclusion. For example, calligraphy, itself “archaic,” appears throughout The Book of Ours, gorgeous and polished, but it appears inconsistently, along with less polished penmanship.

4.Circles

The Book of Ours draws us back to the archetype of circle and cycle; positively and negatively intertwined, signifying hopeless repetition and also renewal, or repetition as transformation:

And the CIRCLE

Of homelessness itself (March)

Rough sleep. SHELTER. Outside once more (April)

Pregnant, homeless, skeletal, autumn. Reunited

Don’t get yourself lost in circles

Wheels on fire, rolling down the road (October)

At the same time, the poet sings: “We are satellites stars surround us,” as do the seasons that give comfort, excitement, rest, and renewal, all marked in the book itself. A great act of imagination and artistic imagination bring the makers from circles of despair caused by the circle of homelessness itself to at least a vision of belonging to the cosmic cycle; note the mysterious juxtapositions in “Pregnant, homeless, skeletal, autumn. Reunited” — belonging to both versions of the circle at once.

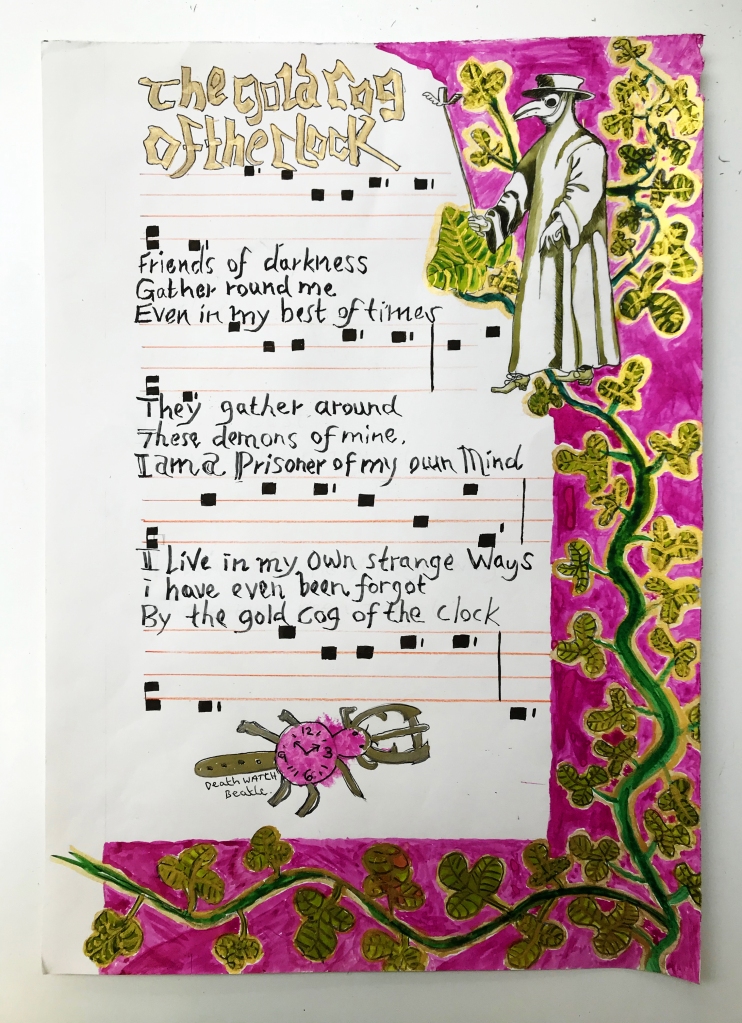

When the sun coming up

The golden cogs of the clock.

Usually representing mechanical circles, here the cogs belong to the generative source of the sun. The second line has been snatched from Lawrence’s poem and song, being made to live again in a new context. “Round”ness becomes support and even transformation: “the seasons bring us round again.” In the midst of the cycle of an expression of malign and indifferent forces controlling one’s subsistence emerges the will and the vision: “you can TURN things around better. The following calendar lines from October, each line composed by a different person, are heart-rending; they convert private pain into a vision of cosmic coherence:

You broke it all. Start again

Please don’t punish me again, God.

My being belongs to the elements.

The first line re-evaluates brokenness because after the full stop is a petition for new beginning. In the fatalistic imagery of circles, “broke” layers personal failure but with a consciousness of the interruption of failure’s grim cycle. To start again is to renew a cycle but now on one’s own terms. The “again” in the second line, addressed imploringly to God, is a brief prayer against resignation and helplessness and pain, but invoking the divinity, it at least reaches beyond the immediacy of one’s material existence as perhaps a point of self-recognition. The centrality of the cosmos in A Book of Ours indicates the TURN towards that realignment: “We are satellites. Stars surround us.” .

5. Monuments

“Adam’s Curse,” (2) refers to labor as the curse, but The Book of Ours celebrates that labor and reveals laborers as an at least temporary community: a monument of labor is a contradiction that reflects a takeover of a tradition by the people who actually constructed it. A monument, religious or secular, takes its viewer or reader out of the world of daily life into a vision of undiluted power. The audience is stunned, transported. The Book of Ours, itself a monument, draws its audience into a stimulating confusion. The Book of Hours encourages reflection, interiority and prayer; and The Book of Ours?—

NOTES

- Allen Fisher

- W.B. Yeats

WEBLINK